I built an integrated population model and showed that despite a high immigration rate in the first years, the productivity of the population has been in constant decline since the beginning of the recolonization.

The difficulties in understanding the underlying reasons of a population decline lie in the typical short duration of field studies, and the often too small size already reached by a declining population. However, using these restricted dataset, it is needed to disentangle the relative potential responsibilities of multiple environmental factors that can interact to influence population dynamics. Using both spatial and temporal variation in population size, I showed the decline of the hoopoe population was mainly caused by the decrease in first-year survival and the number of fledglings produced. I was able to quantify the relative contribution of climatic factors, degradation of habitats and research activities on the decline of a population of hoopoes.

Context

The hoopoe (Upupa epops) population monitored by the Swiss Ornithological Institute breed in the valley of Sion in the Swiss Valais. The intensification of human activities has caused a quasi‐disappearance of natural cavities on which hoopoes relied for breeding. From 1999 to 2003, more than 700 nest boxes were installed in the study area as a mitigation measure. The number of broods increased sixfold in the following years, but has been in steady decline since 2006 that is, just after reaching its demographic peak. In the project led by the Swiss Ornithological Institute and the University of Bern, I studied the causes of this decline using the 16 years of population monitoring from 2002 to 2017.

Challenge

How can we succeed in understanding the causes of the current decline of the Hoopoe in the Swiss Valais, using a small amount of data to unravel the relative roles of multiple potential factors that interact at different scales?

Approach & Results

To reach this goal, I followed a three step analysis. I built an integrated population model structured by habitat. A retrospective analysis of this model allowed me to quantify the contribution of each habitat‐specific demographic rate (survival , immigration, probability of hatching, number of fledglings produced) to the variation in the population growth rate and to the decline of the population.

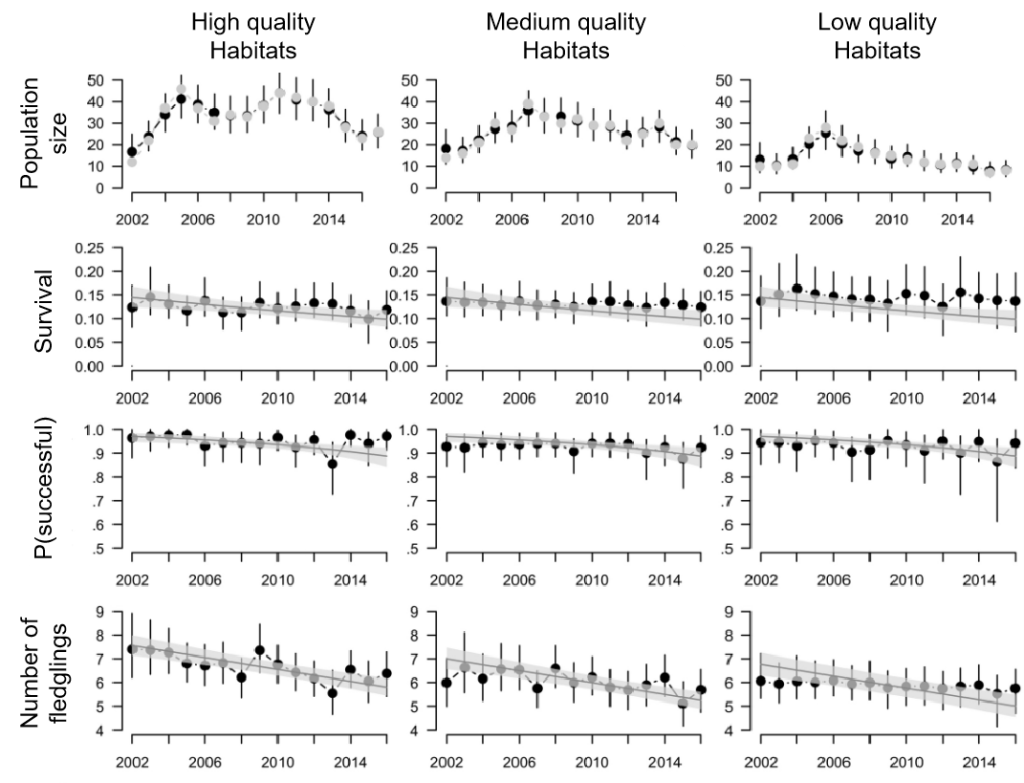

Second, by including trend analyses in this model, I identified which demographic rates had decreased and I examined if this decrease was similar among habitats of different qualities. These first two steps allowed me to demonstrate that the decline of the hoopoe population was mainly caused by the decrease in first-year survival and the number of fledglings produced, especially in high-quality habitats. Since a majority of pairs bred in habitats of the highest quality, the decrease in the production of locally recruited yearlings in high‐quality habitat was the main driver of the population decline despite a homogeneous drop of recruitment across habitats.

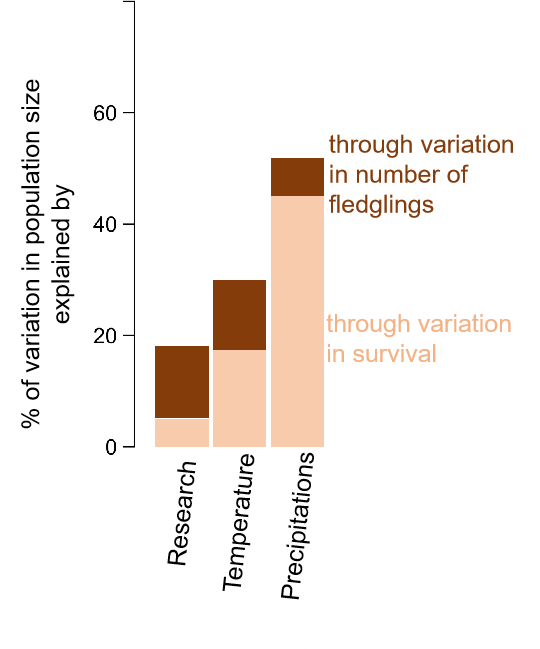

Finally, I studied the influence of climatic conditions and research activities on the decrease in population growth rate. Variation in precipitation and temperature that had become increasingly unpredictable for hoopoes were responsible for 15% of this decrease. Of this 15% decrease, 3% was caused by the research activity, and especially by the reduction of the delay between captures of breeding females and their hatching date. This premature capture negatively influenced brood productivity. A delay in female captures since 2016 has allowed the population to achieve a higher productivity again.

Project leader and Collaborators

- Michael Schaub & Marc Kéry: Swiss Ornithological Institute, Sempach, Switzerland

- Raphaël Arlettaz & Alain Jacot: Division of Conservation Biology, Institute of Ecology and Evolution, University of Bern, Switzerland